Escaping the Growth Trap

Economics of Nature

Robert Costanza is most well known for publishing a paper in 1997 on “The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital” in which he and several colleagues estimated the worth of the biosphere to be (conservatively) around 175% of global GDP. ($33 trillion USD per year natural capital versus $18 trillion USD per year GDP.) 1 The problem is all this value (and exploitation of value) is outside the global economic system. Robert Costanza covers this, and more, in his book “Addicted to Growth: Societal Therapy for a Sustainable Wellbeing Future”

I originally picked the novelette up because I was impressed by his responses to two other environmentalists in an online debate. I’m interested in wellbeing economies and economic implementations of non-economic values. Having read it I would summarize the book as “not wrong, but not illuminating either.”

The book in question.

So How are We “Addicted to Growth”?

Global GDP measures the total value generated worldwide every year. Its been used as a metric to indicate economic progress and societal wellbeing. There are good reasons we use GDP - foundational development enables tons of things: health, wealth, education, comfort and safety. GDP was much more relevant to wellbeing during the time it was implemented. Things are a bit different now and using GDP to approximate national wellbeing has some serious problems. To make matters worse, there are some indications that GDP has reached a threshold and is no longer connected to genuine progress, at least as measured by the Genuine Progress Indicator.

GDP has a whole slew of externalities (things of value that aren’t accounted for). From the work of stay-at-home-partners, to “owned durable goods,” volunteer work, and charitable donations. In addition, increased expendatures like healthcare, pollution cleanup, and flood prevention are all positive in the lens of GDP. Expendatures are considered positive even when they are restoring value that was destroyed. Externalities cause serious misallocation of resources. They incentivise harvesting past sustainable yields, polluting rivers, chopping down rainforests, draining groundwater, etc. But solutions are difficult - measuring the True Cost (including end-of-life disposal!) of every product would be prohibitively expensive to evaluate and track.

True wealth.

Fortunately there are many examples of potentially better indicators of national success. Bhutan’s “Gross National Happiness”, “Wellbeing Economy Governments” (Scotland, Iceland, Finland, New Zealand, Wales), the aforementioned “Genuine Progress Indicator”, the “Human Development Index”, the “Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare”, the “Inclusive Wealth Index”, “the Degrowth Accounts”, “OECD Better Life Index”, “Social Progress Index”, “Legatum Prosperity Index”, “World Happiness Report”, and probably more.

Societal Traps

In the same way that people can go haywire and fall into personality traps and addictive behaviors, there are societal traps which cause us to get stuck in collective death spirals. The most famous one being the “tradgedy of the commons.” There are many more examples.

- Its possible to get stuck in ever-increasing labor disputes where both sides lose.

- Sunk cost fallacies can lead to truly heinous outcomes.

- Our cultural norms seem to drive members of society towards material wealth at the expense of assets which would actually give us greater happiness: family and health.

- Costanza sprinkles in some cute demostrations of rational decisionmaking leading to irrational outcomes: The “dollar auction game” and the “ultimatum game.”

This is all to show that these sorts of societal traps exist, and we are still learning to recognize and avoid falling into them.

After you fall prey to a personal or societal trap, there are still some techniques to escape them. It is tempting, but confrontational approaches and accusations famously have been shown not to work at any scale.

- Motivational Interviewing works and can scale to society-wide efforts.

- Shared visions of plausible scenarios for the future are powerful catalysts for change.

The book then details how to go about scenario building with the input of thousands. South Africa ⭳, New Zealand ⭳, the United Nations, and various megacorps have already practiced this and provide examples both of scenario building techniques, success, and of course the scenarios of plausible futures themselves. The one Costanza is most enamored with is the Great Transition Initiative. Come to think of it, Jackson and I recently participated in a scenario building competition ourselves. It was put on by the Future of Life Institute.

Having a utopic vision is important. Honestly this has been inspiring me in small ways ever since we concocted it.

Other techniques to escape societal traps rely on social trust or social capital. These provide the coordination power to climb out of negative behavioral spirals. Unfortunately this is another type of capital that is outside GDP!

The 4 types of capital Costanza highlightes are “Social Capital”, “Natural Capital”, “Built Capital” and “Human Capital”

| Type of Capital | Description |

|---|---|

| Natural Capital | Ecosystem services, water, food, fuel, fiber, climate, and other conditions for robust life cycles. |

| Social Capital | Social networks, rules, norms, cultural heritage, good governance, cooperation potential, trust. |

| Built Capital | Physical stuff. Factories, roads, buildings, machinery, orchards, tools, communication lines. Things that make value easier to produce once they exist. |

| Human Capital | People power. Knowledge, mental and physical health, creativity, inventiveness, all modes of human capacity. |

Costanza’s Scenario

Costanza then gives his own realistic future scenario, citing lots of electronic and social technology that already exists and has been tried somewhere in the world. He mostly collects good ideas and supposes we adopt them widely. I thought he did a good job constructing a realistic and yet utopic scenario. I don’t have a lot of commentary to offer on it, but I do recommend reading it. It’s both a good resource and a good exercise in critically evaluating what we should be working toward.

The chapter thereafter elaborates on these policies and the evidence to support them. Example: Common Asset Trusts and Sociocracy. Lastly he ends the book with a list of things that have gone right for us recently: from renewable energy to regenerative farming.

Sociocracy organization for scaled up consensual decision making.

Retrospective

This doesn’t come across from my summary, but from the outset I couldn’t read the book without being fustrated by a fundamental oversight. To put it simply: The tradeoff between natural wealth and economic wealth.

Costanza and I agree that previously there was plenty of natural wealth to go around, so it made sense in the past to trade it for growth and GDP. Now Costanza acts like we are well into a hole and have to turn this ship around immediatamente. I’m less sure. I think technological advancement, economic wealth, and the rest of human progress are immensely valuable. Especially when tech advancement so often makes earlier frugality pointless. It’s not opaque to me whether natural wealth is to overtaking economic wealth in value.

This says slowing down would have been a mistake.

No really, I actually have no clue. Even setting aside tech advancement, it could be we are in the red, or we could have centuries to go. I don’t know. And I don’t know how to have a grasp of our global prospects. If there is still plenty of extra natural capital, then we should keep this train going awhile longer, regardless of the Planetary Boundries looming in the distance. If that’s not so, and economic development is paltry in comparison, then Costanza has the right idea. I don’t think I have seen any sort of evaluation laying out when is the right time to reverse direction. I see lots of warnings, but many of them are things like the “6th Mass Extinction”, “overpopulation”, “peak oil”, and so on uttered in the same breath as “we need to stop YESTERDAY!” But the “6th Mass Extinction” is about 500 years off, overpopulation is ending on it’s own, peak oil has been solved by renewables and so on. Environmentalists have been inaccurate about how far off threats are and how valuable progress and human civilization is. But everyone else is misguided about how valuable natural capital is! So I’m left in the dark.

This was a total upset of expectation, but a truly welcome one.

I haven’t seen a serious analysis of exactly when the time to shift gears is, according to what tradeoffs. Its not obvious to me that we should come to a screeching halt, a stern halt, a leisurely halt, or plan our halt for next century. Even if that time has already come and gone, I still haven’t seen any graph demonstrating where the lines crossed and the costs outweigh the benefits.

This says we are probably in the red.

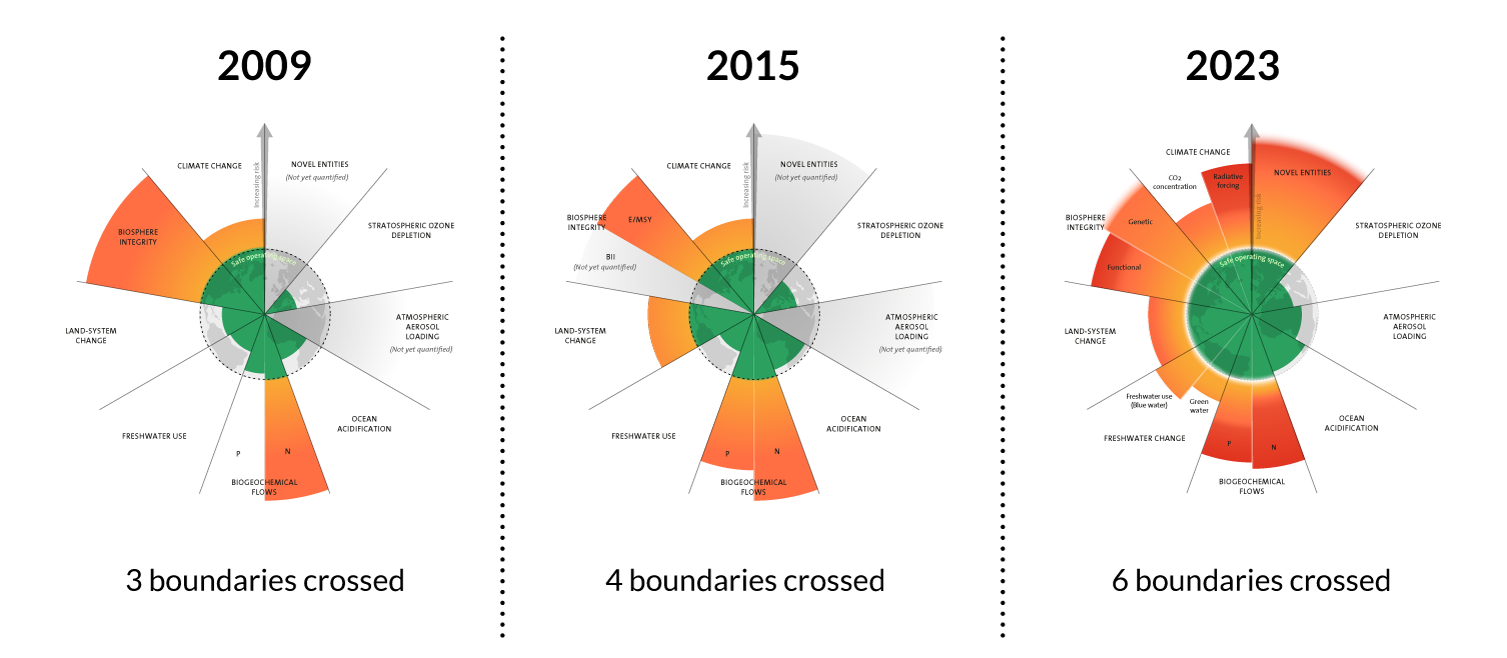

The 1.5 / 2.0 / 3.0, degree global warming thresholds are the sort of thing I am looking for. Its explicit about the tradeoffs we are making. But global warming only captures one aspect of our expansion and exploitation. The planetary boundaries are another great example, capturing multiple aspects. But its hazy what the tradeoffs and exact repurcussions are. I suspect the 30% earth for ecosystem services statistic is accurate, but I don’t understand how close we are to that nor how bad it will be when we overstep it. Restructuring our entire society is a LOT. Where is the graph describing when circular economics is the answer.

- More recent estimates back this up: 41.7 trillion USD (55% of GDP) by the Swiss RE institute. Nature’s subsidies amount to an annual US$4-6 trillion, or approximately 5-7% of global GDP according to the Das Gupta Review ⭳. The World Economic Forum suggests that industries highly dependent on nature generate 15% of global GDP ($13 trillion), while moderately dependent industries generate 37% ($31 trillion). [return]